Dear Esther - Chasing ghosts

Dear Esther, the first-person narrative game published in 2012 by The Chinese Room, has been a surprisingly seminal title with numerous indie titles following its steps to explore the narrative possibilities of the very framework we usually associate with shooters.

On top of proving a useful template for the whole "walking simulator" niche, it offers a fascinating perspective on how story merges with gameplay and -thanks to a very unusual Italian translation- on how we can translate it.

A shadow

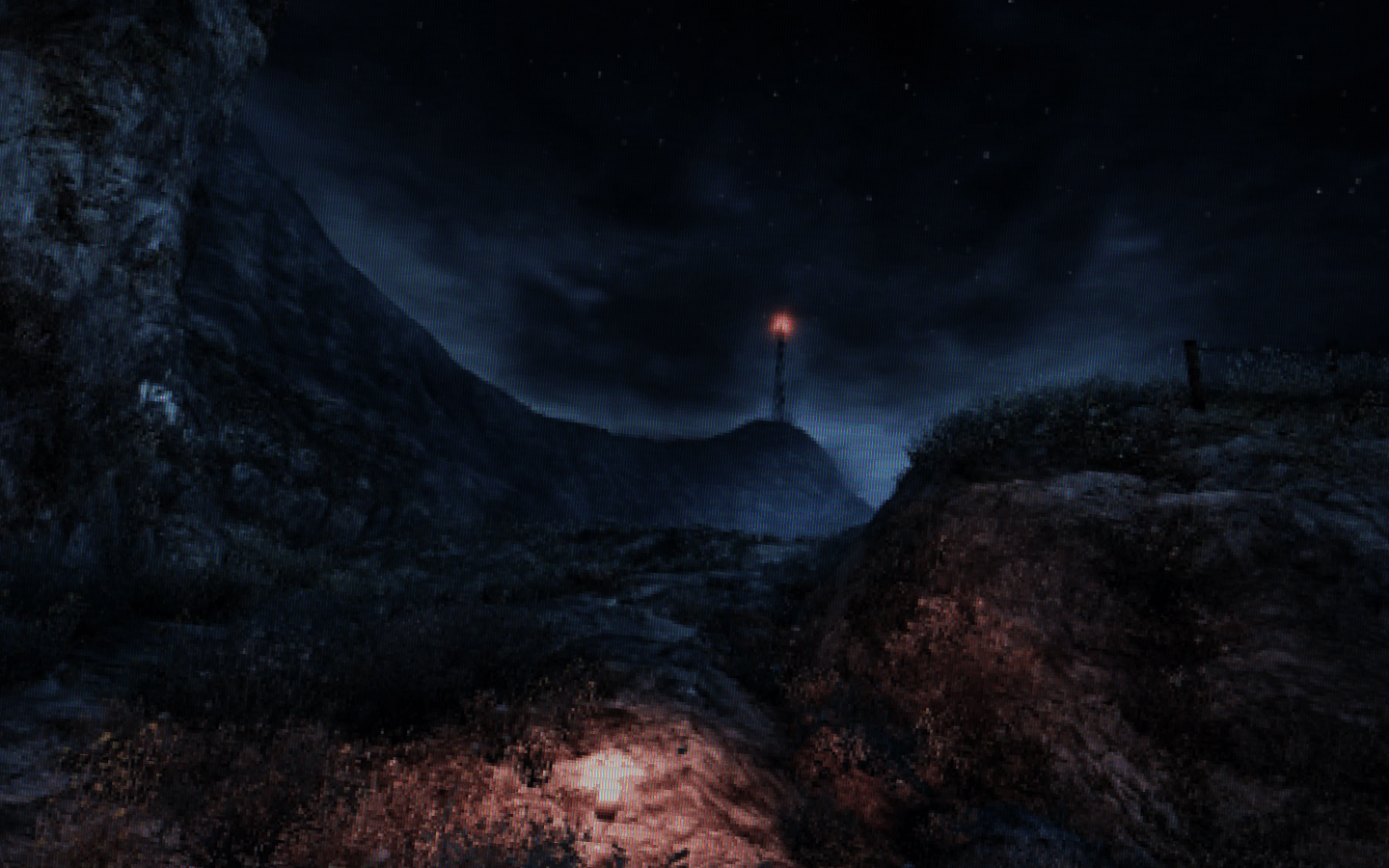

Near the end of Dear Esther, there is a moment that sums up the whole experience. You have walked in complete solitude for about two hours when the path opens to shows a small cliff in the distance. There, next to a lit candle, you see a shape against the fog. It's all very dark, but it's unmistakably a human figure.

You hearts skips.

As the path twists down before climbing up to the cliff, you start to picture what you might do, see, or say...

Then you reach the top and... there's nothing at all. The figure has vanished without a trace and you wonder what you really saw.

The structure

Dear Esther was deliberately created as an experiment in videogame narration. As explained in this interview, it tried two things:

- Removing all the gameplay elements from an FPS environment, pushing the player forward through story alone

- Harnessing the visceral immersion that characterizes FPS to tell a deliberately convoluted, non-linear story

How these goals have been achieved? And how they impact translation? Let's see it together.

Gameplay

As we can expect from above, the “game” element of Dear Esther is truly minimalist, almost vanishing into the conventions of 3D gaming.

As a player, you can walk around the 3D landscape using the WASD keys and look around with the mouse. As you cannot grab objects around you, nor jump or climb, your only aim is to find the “good” path forward, like in a labyrinth of sorts.

The correct path shows new locales and triggers bits of narration, while the wrong ones bring you back to old locations (back tracking) or, if you fall from a cliff or into the sea, "kill" you with a black screen - after which you reappear in the last safe position before the fall.

Non textual narrative

In order to draw you in, Dear Esther uses mystery and unease.

You start your travel as a lone man on a desert island. In eerie solitude, you move towards the only sign of life you can see: a blinking aerial in the distance.

Initially, everything seems to fit the “desert island” narration, but a mysterious music and sound effects already hint that more is to come.

As you move forward, things get increasingly incongruous. Why the hut of a shepherd has an ultrasound picture on the table? Who really made those huge paintings? Who lit the candles along the way?

These, and even more irrational elements, destabilize the narrative, taking our certainties away with it. "Where I am? Who is my avatar? What is actually real?"

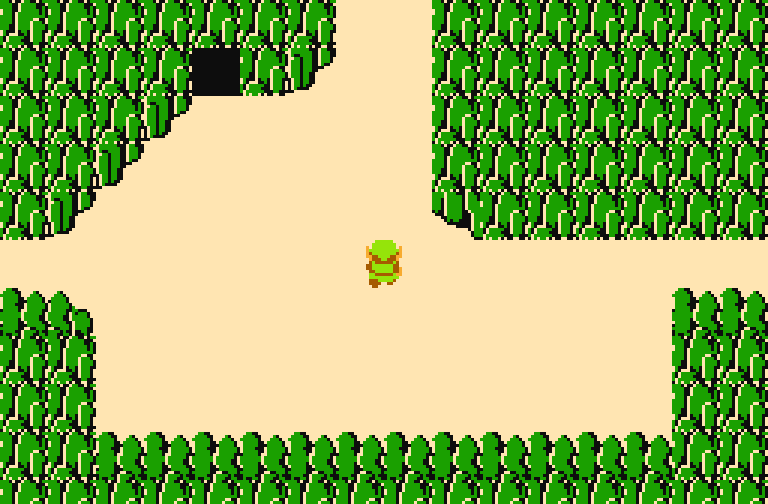

If you had a NES in the 80's, you probably remember this scene:

It was the very first thing you saw in the Legend of Zelda, and you substantially had no clue about who you were and what was going on.

All you knew was that you had a scary looking entrance in front of you, and maybe monsters round the corner. The feeling of uncertainty was quite uncomfortable (especially for a young kid).

In some way, the Legend of Zelda was about solving that tension. Each fight, boomerang and bottled fairy was a step towards dominating this world until nothing could scare you anymore.

Dear Esther never allows you to do that. Through constant manipulation and self deconstruction, it constantly pushes you back to the state of curiosity and anxiety you had in that Zelda screen, and makes you yearn for explanations.

Time has told us that this surrealist element, this deliberate undermining of the logic and familiarity we gradually build inside the game world is probably one of the main strength of the "walking simulator" sub-genre, and the area where it arguably gets more poetic and inspiring.

Textual narrative

All we know about the setting and its characters is conveyed by disembodied voice overs, played at specific locations along the way. They mostly contain letters to a certain "Esther" and commented excerpts from an old book about the Hebrides islands, on which the game is set.

They are ambiguous and non-linear in two ways.

One is purely textual: the audio cues are given without any context or explanation and are obscure and conflicting, forcing the player to pick and choose what he wants to believe in.

The other is born out of software and gaming. As the voice overs are randomized, each play-through will tell a slightly different version. The game reality is always shifting, so there simply cannot be a single truth.

The end result is a "mood piece" that doesn't really have a message at its core, but still proves an engaging experience through the emotions it stirs within each player and their imagination.

As a player, I was amazed that Dear Esther would still give me goosebumps after 5/6 full play-throughs. But as a translator, I just loved its minimalist structure because it let me see each mechanism at work, almost like an engine cutout of game narrative.

The translation

So, how would you translate this title? Well, the interview tells us more about the text itself.

Its creation was deliberately free-form, like a "stream of consciousness". The beginning was clearly defined, with the starting theme of being stranded on a desert island. And the ending was too, with the idea of the infection/transformation to be resolved through the jump from the aerial and the parallel with the Paul conversion/Road to Damascus story.

But everything in the middle grew organically, feeding back from and into the music and map creation and deliberately trying to go in several, evocative directions at once.

The American novelist Philip K. Dick, with novels like Lies Inc., is quoted as a personal source of inspiration, specifically for their style that seeks a coherence of vision more than a linearity of meaning.

Quite surprisingly, the official Italian translation for this game, donated by the now retired indies4indies group, searched another track 100 years ago.

Dear Esther has been created by some exquisite actors and theater musicians. Discussing with it author, professor Pinchbeck, I found out that he was a big fan of (19th century Italian dramatist and novelist) Luigi Pirandello. Therefore, before staring work on his text, I suggest to try something different: a slightly antiquated writing to homage our great dramatist (needless to say, I told him there would be some minimal differences with modern Italian). He was delighted of my suggestion and he approved it on the spot. (Paolo Rostagno Giaiero, Arsludica)

For that reason, the translation for Dear Esther is deliberately archaic both in terms of spelling and terminology. The idea was very original, and the possibilities fascinating, but I have two major concerns about the results.

The first one is that ambiguity was a core element of this experience, constantly alternating madness and normality.

This was served by a text that, despite a penchant for rich and complex words, was never strongly characterized, not even when quoting the writings of Donnelly the cartographer.

However, the new style adds an inexplicable element from the outset: why is this story set in modern UK, complete with antacid yogurts, car accident and food chains, mysteriously written as Pirandello would have done it in Italy and 100 year before?

The second one is that the archaisms make the text less instinctive. I often found myself mentally “editing out” the additional style in order to lose myself again into the flow of speech as it was originally intended.

A bad work? Not at all: the translation is extremely careful and clearly a labor of love, it's just a shame that it end ups feeling a bit disjointed and artificial. In the end it was an experiment, surely worth of a bold creation like Dear Esther.

When I first did this study in 2012, it taught me a lesson I still follow today: serve the game. In this case, Rostagno did an amazing work at a purely textual level, but it didn't work because it played against the strengths of the game itself.

Working on flat Excel files, we naturally tend to see out text like a book, but we should always remember that interaction is a delicate, living thing and that we must do all we can to make it thrive.